This project will address methods to adapt beach and dune nourishment to improve resilience in a changing climate. As storms become more powerful and seas continue to rise, major erosion events will occur more frequently. However, coastal communities do not yet understand how to evaluate their increasing vulnerabilities and adapt their long-term planning. In this project, we will identify the climate patterns that most often trigger the need to nourish, the variability of the time interval between such nourishments, and the economic costs and sediment volumes necessary to maintain this coastal protection policy into the 21st century.

A stochastic climate emulator will first be developed to simulate 1000s of realizations of chronological climate patterns (forced by satellite and GCM products) to create future storm events coupled with sea level rise scenarios. A library of high fidelity, open source, hydrodynamic and morphodynamic simulations (ADCIRC+SWAN and XBeach) will then be used to develop a surrogate model to predict erosion and flooding for each future realization. Triggers like beach width, dune height, and community preferences will be used to identify how often communities will need to re-nourish, contingent on future climate and sea level rise scenario.

JC Dietrich, DL Anderson. “Sustainability of Barrier Island Protection Policies under Changing Climates.” U.S. Coastal Research Program, 2019 Academic Research Opportunities, 2019/10/18 to 2021/10/17, $226,624 (Dietrich: $226,624).

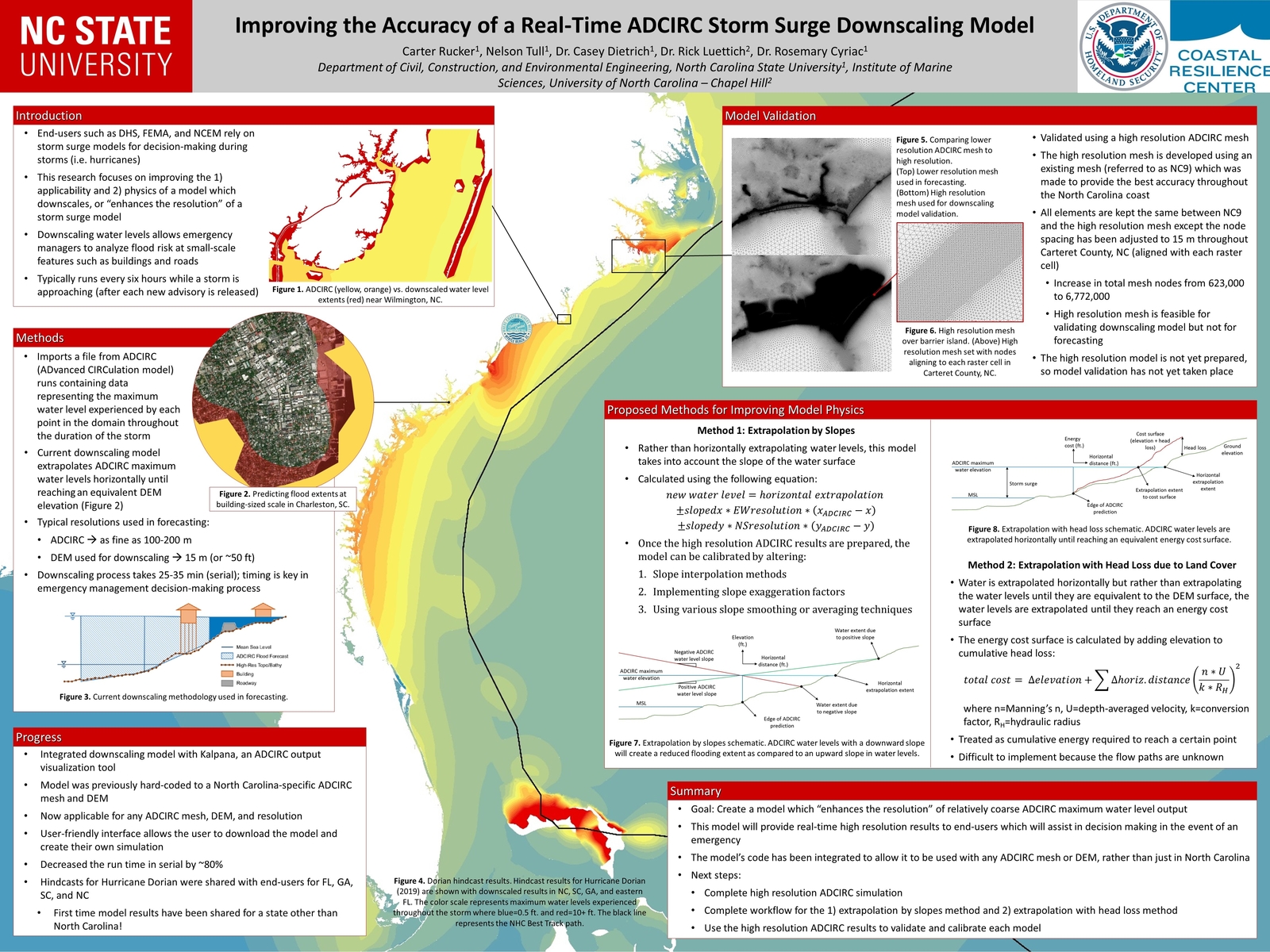

Averaging techniques are used to generate upscaled forms of the shallow water equations for storm surge including subgrid corrections. These systems are structurally similar to the standard shallow water equations but have additional terms related to integral properties of the fine-scale bathymetry, topography, and flow. As the system only operates with coarse-scale variables (such as averaged fluid velocity) relating to flow, these fine-scale integrals require closures to relate them to the coarsened variables. Closures with different levels of complexity are identified and tested for accuracy against high resolution solutions of the standard shallow water equations. Results show that, for coarse grids in complex geometries, inclusion of subgrid closure terms greatly improves model accuracy when compared to standard solutions, and will thereby enable new classes of storm surge models.

Averaging techniques are used to generate upscaled forms of the shallow water equations for storm surge including subgrid corrections. These systems are structurally similar to the standard shallow water equations but have additional terms related to integral properties of the fine-scale bathymetry, topography, and flow. As the system only operates with coarse-scale variables (such as averaged fluid velocity) relating to flow, these fine-scale integrals require closures to relate them to the coarsened variables. Closures with different levels of complexity are identified and tested for accuracy against high resolution solutions of the standard shallow water equations. Results show that, for coarse grids in complex geometries, inclusion of subgrid closure terms greatly improves model accuracy when compared to standard solutions, and will thereby enable new classes of storm surge models.

Averaging techniques are used to generate upscaled forms of the shallow water equations for storm surge including subgrid corrections. These systems are structurally similar to the standard shallow water equations but have additional terms related to integral properties of the fine-scale bathymetry, topography, and flow. As the system only operates with coarse-scale variables (such as averaged fluid velocity) relating to flow, these fine-scale integrals require closures to relate them to the coarsened variables. Closures with different levels of complexity are identified and tested for accuracy against high resolution solutions of the standard shallow water equations. Results show that, for coarse grids in complex geometries, inclusion of subgrid closure terms greatly improves model accuracy when compared to standard solutions, and will thereby enable new classes of storm surge models.

Averaging techniques are used to generate upscaled forms of the shallow water equations for storm surge including subgrid corrections. These systems are structurally similar to the standard shallow water equations but have additional terms related to integral properties of the fine-scale bathymetry, topography, and flow. As the system only operates with coarse-scale variables (such as averaged fluid velocity) relating to flow, these fine-scale integrals require closures to relate them to the coarsened variables. Closures with different levels of complexity are identified and tested for accuracy against high resolution solutions of the standard shallow water equations. Results show that, for coarse grids in complex geometries, inclusion of subgrid closure terms greatly improves model accuracy when compared to standard solutions, and will thereby enable new classes of storm surge models.